Scrapbook's Aesthetes & Artists series presents Bhasha Chakrabarti

Artist Bhasha Chakrabarti talks about mending, materiality, and confronting fragility, vulnerability, and impermanence.

Scrapbook is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. For those who already have, I’m deeply grateful.

This week, I’m delighted to feature the work of artist Bhasha Chakrabarti as part of the Aesthetes & Artists series, which explores how contemporary artists reshape myths and narratives, in the age of polycrisis—a term describing overlapping global crises – and non-alignment, historically rooted in geopolitics. We ask, what is the relevance and purpose of art and myth-making in today's complex world and its impact on humanity's shared values and future.

Bhasha’s work resonated with me for several reasons, not least of which was the materiality of the work, but also the links between the new and old. The idea of the ‘Ajeeb’ , the strange, the oddity…really stood out for me. Offering as it does possibilities of the uncanny. Her work is currently showing at the Armory Show in New York, at Experimenter Gallery, Booth 308, definitely a must see! Enjoy the interview!

What do you create, what drives you to pursue this creative work?

My work engages with the way that cloth simultaneously covers and reveals. The physical proximity of cloth to the human body, both when being used and when being produced, gives it the unique ability to hold the complexity of subjectivities and labor. Thus, I use textiles in multiple and synchronous forms: as a support and a subject matter in painting, as a wrapping and a surrogate for skin, and as a material manifestation of and a metaphorical container for human entanglements throughout histories of oppression and liberation.

The centering of cloth in my work, is the centering of embodied touch, both violent and erotic; gesturing to the actuality of ruptures in society, as well as the possibilities of mending, patching, and being quilted together in radically new ways. I see mending as a creative gesture that confronts fragility, precarity, and impermanence, while embodying hope, continuity, and futurity. Unlike many other forms of repair, the slow, quiet, and often collective process of darning, piecing, and stitching used or damaged clothing is most often relegated to women and occurs in domestic spaces. This, along with leaning into the richness of non-Western textile traditions, becomes a unique way of resisting colonial and capitalist systems that deny the existence of black and brown bodies as sites of pleasure, knowledge, and value.

Bhasha Chakrabarti, New American Odalisques

The body is implicitly present in cloth and it is often explicitly present in the imagery of my paintings. I am particularly interested in intervening in Western histories of painting the nude body through a lens of idealization and objectification. Rather than responding to this devastating praxis by covering up or obscuring the nude, I choose to lean into a performance of excess nudity and, often, eroticism. This approach utilizes brown jouissance, defined by Amber Jamilla Musser as the knowledge producing sensuality and sexuality which resides within the fleshiness of the brown, femme body and exceeds the constraints of objectification that are constantly placed upon it.

What sustains and motivates you in your creative practice?

My practice places equal importance on the visual content of painting, the performativity of the act of painting, and the materiality of the cloth on which paintings are made. I also continuously draw from South Asian, Hawaiian, and African-American aesthetic traditions in order to recalibrate the dominant epistemological hierarchies which are otherwise dependent on willful erasure. I am always attempting to exercise what philosopher Jonathan Lear calls “radical hope”. This is not to be confused with blind optimism, but rather encourages sitting with, or stitching with, vulnerability and ambivalence, while maintaining a commitment to equity and justice. Thus, I continue to explore how painting can function as a mode of public discourse rather than being a self-contained discipline.

My commitment to art-making is therefore to an excavation of pre-existing historical intimacies across the global South, to acknowledging and making visible existing interdependencies between marginalized communities in the North, and to imagining solidarities and alternative futures.

What is the best book you’ve read this year, and what impact has it had on you?

The Doll's Alphabet by Camilla Grudova. My friend and fellow artist, Afrah Shafiq recommended it to me and it was really wonderful. It's a collection of short stories which are extremely uncanny and embodied. I've been thinking a lot about the "ajeeb" (strange) and these stories were very ajeeb indeed.

Which recent artwork has resonated with you deeply, and what about it stayed with you?

By recent artwork if you mean an artwork I encountered recently: I was recently shown this miniature painting from Kishangarh circa 1740, referred to as "By the light of the moon and fireworks".

BY THE LIGHT OF THE MOON AND FIREWORKS, ATTRIBUTABLE TO BHAVANIDAS or NIHALCHAND, RAJASTHAN, KISHANGARH, CIRCA 1740

It's only 8.5 inches x 6 inches but it's so layered, enchanting, and bizarre, both in terms of technique and in terms of what's depicted. I've been thinking about it for days. Every centimeter of this painting is packed with information, but it's also so poetic.

If you mean an artwork made recently: I saw this film titled "Summer Solstice" directed by Noah Schamus which has been haunting me. It's about friendship, sexuality, and race, without any platitudes or preachy-ness. It's so nuanced, simple, and inconclusive in a way which I love. It's not passing judgements or giving a positive or negative valence to any emotions, which is what I think makes the most successful artworks, regardless of medium. One is left with a deep, thoughtful discomfort.

Summer Solstice follows Leo, a trans man, and his cisgender, straight friend Eleanor go on an impromptu weekend trip, during which they uncover some old secrets, some new challenges, and find the answer to the age-old question: can bad sex and good friends mix?

What recent play or performance has moved you, and how did it affect you?

Jeremy O. Harris's "Slave Play" was really impactful for me. I think it talks about sex and daily power dynamics in a really nuanced way. It doesn't try to flatten any complexities and yet manages to have this relatability to it, that allows you to enter the work. Again, one is left with that deep, thought-provoking discomfort.

Slave Play by Jeremy O. Harris

Is there a place that holds significant meaning for you? What makes it special?

Many! But I'll say Hawaii. It's where I grew up and it has deeply impacted my work. Growing up in Hawaii, I was exposed to Hawaiian mythology, music, and dance as equally valid ways to approach and understand the world, as Western science, history, and logic. This expanded possibilities of knowledge for me which continues to be essential to my practice today as I consider all the ways in which we “know” through our minds, hearts, and bodies.

Bhasha Chakrabarti, Genealogy (Old & New) 2023, photographed with me holding it up in the valley I grew up in, Manoa)

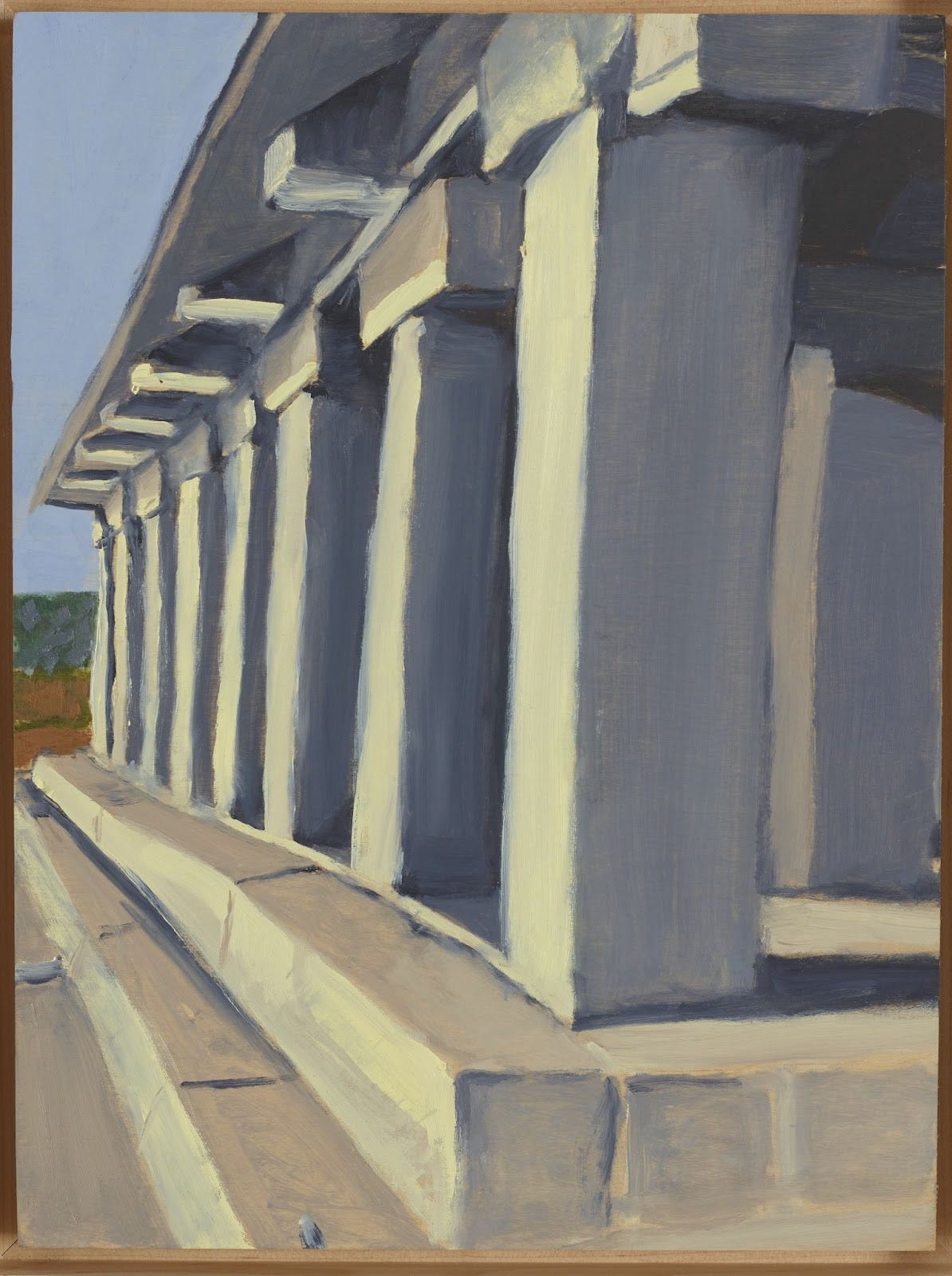

Is there an architectural space that intrigues you? What about it captures your interest?

I recently spent a few months living and working in Hampi. There was a particular "mandapa" (pillared pavilion) in the nearby village of Anegundi which I've become obsessed with. It's dated to the mid-1500's and is said to have been the site of the famous king, Krishnadevaraya's, cremation. Compared to a lot of the other beautiful and intricately carved Vijayanagar Empire ruins that surround it, it may seem simple and unremarkable. But its simplicity is part of what makes it so stunning. But the most remarkable thing about it is that it has 64 pillars, particularly in reference to the 64 arts/kalas according to ancient Sanskrit texts. So each pillar corresponds to an art, and these arts range from painting, dance, and music, all the way to the art of telling a joke, mixing cocktails, and even making the bed.

Bhasha Chakrabarti

Bhasha Chakrabarti

What questions are you exploring this year, whether they relate to art, the environment, or another area of interest?

I mentioned briefly, I've been really delving into notions of "ajeeb", and what makes something ajeeb? Both in terms of strangeness/othering as well as its connection to the Arabic root word "ajaib", which refers to wonder. I love that the hindi/urdu word for museum is Ajaibghar, a house of wonder, a house of strangeness. I'm really interested in how ajeeb has a close intimacy with south asian queerness, and is perhaps an even better term for "queer" in the south asian context. I'm currently working on an exhibition which is centered on exploring how "ajeeb" operates in the Ismat Chughtai short story, Lihaaf, and ways in which the home, the most familiar place of all, can start feeling strange and wondrous.

Bhasha Chakrabarti, A Study of Limbs and Lihaaf (California King), 2020, Oil, used clothing, thread, and fiber glass on linen

What is the best advice you’ve ever received, and why has it been meaningful to you?

Ah, I'm constantly absorbing advice from around me, so it's hard to pick the best. But perhaps the one I try the hardest to follow is to always prioritize and follow friendships over "work" or other predetermined paths to success. Friendships build the most meaningful works and ultimately lead to a much more secure and fulfilled version of success and happiness. (related to this, I've attached a painting of two of my best friends, titled "The Sunbathers" from 2021)

Bhasha Chakrabarti, The Sunbathers, 2021

Bhasha Chakrabarti (b. 1991) has been based in Honolulu, New Delhi, New York, and now lives in New Haven, Connecticut. Her work is currently showing at the Armory Show in New York, at Booth 308.

Thank you for your support of Scrapbook. If you would like to share with a friend, click here.